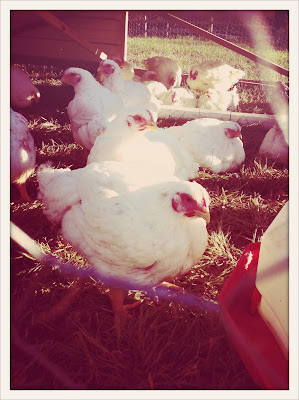

So it's been a pretty exciting and busy week in a lot of ways, but for now I'm just going to focus on what happened in the poultry world.

We processed our Cornish X chickens last Thursday (which is a polite way of saying that we slaughtered and dressed them). These chickens have been quite a handful. Despite our best efforts, we've lost about a third of them over the last eight weeks. A handful died as chicks, either because they were weak or got smothered. Then, about a week after we put them outside, we had a very cold and rainy stretch towards the end of May. We think they were weakened by the bad weather, and that contributed to a number of them getting sick, most likely from a parasite called coccidia (we noticed bloody stool in their pen). Then, only two days from our scheduled chicken processing date, we had an exceptionally warm Tuesday and the chickens overheated. We went down to check on them after lunch to find over a half dozen dead or dying. It was heart-breaking.

These incidents aren't very easy for me or Dave to talk about. We are responsible for these animals, and when they die there is no denying that it is usually almost entirely our fault. Mostly, we make ourselves feel better by telling each other how we will never make the same mistakes again - hopefully this is true. At the same time, we are getting better at coping with the feeling of loosing one of our animals. There's a cliche about how living on a farm brings you closer to understanding and accepting death - so far, this

is true.

In this case, however, there is no denying that it wasn't just our inexperience that caused so many of these chickens to die. For our first experiment with meat birds we decided to get all Cornish X chicks, one of the most popular breeds of meat chicken. The Cornish X is bred to grow fast and large, which in turn makes them less hardy than other birds. Throughout the eight weeks we spent with these chickens, we couldn't help but to feel a little depressed about how helpless they seemed. Cornish Xs have a lower survival rate than other breeds of chicken, they suffer from leg problems and weak hearts, and due to their weight they are very inactive. We have vowed from now on to only buy heritage breed chickens. They might take longer to grow and may never get as big (and they contain less white meat, and more dark meat, which is okay with me), but Dave and I have agreed that we want to raise birds with better instincts. Our new chicks are all

Freedom Rangers and

Dark Cornishes.

As we stood and stared and swore at those seven dead chickens on Tuesday, I felt both guilt and anger. Look at how much food was being wasted! These were our biggest chickens (which probably explains why the heat gave them heart-attacks), they had been gorging themselves on our expensive organic chicken food for eight weeks! They probably totaled 40 lbs of delicious organic pasture raised chicken meat, and they were being thrown into the compost!

It was, by far, the worst day we've had to date.

By propping up one side of the chicken tractor to facilitate a cross breeze, and running an extension cord out from the house to the pen and setting up a fan, we were able to keep the chickens cool through the rest of the afternoon and into Wednesday, which was 95 degrees. Needless to say, we're planning on making some changes to the tractor.

Wednesday night we went to bed early. Dave woke up at 3:30 AM to get the scalder going, and then woke me up at 4:30 so I could help him finish setting up. The forecast Thursday said that temperatures were supposed to be near 100 degrees F, which we were prepared for, but we weren't prepared for the thunderstorms that consistently rolled through

all day. Luckily, we had a tent for the farmers market that provided just enough shelter for the five of us (Dave, me, my mom and two friends) to stay mostly dry.

Dave cut up two traffic cones and built a stand for them, so we could safety hold the chickens upside-down while they bled out. To pluck the birds, we borrowed the scalder and the picker from another farm in town. The scalder fills with water and holds it at consistently 147 degrees F, which is hot enough to loosen the feathers on the bird without cooking it. When we tested it out on Tuesday, the scalder took an unbelievably long time to heat up, so Dave built an insulating wooden box to fit around it to help it reach and hold its temperature. The picker is a cylindrical spinning machine that is filled with little rubber fingers. When the scalded bird is placed inside, the rubber fingers pick off all its feathers. The picker is attached to a hose so the feathers can all be washed out the back as the bird spins. The next step, the eviscerating, was done by hand.

Both Mom and I have done a couple processing days with

Pete and Jen's Backyard Birds in Concord, Dave and I have been doing a lot of reading and I've dealt with my fair share of chickens and knives working in the food industry, so I felt confident that we could process these birds safety and cleanly. We made sure to keep all our surfaces hosed down and sanitized, and we got the dressed chickens iced as quickly as possible. Processing chickens is time-consuming and sticky work, but it was rewarding to know that we were finally producing our own meat.

Which brings me to my next point: when the chickens died needlessly because of a mistake that I made I felt awful, but when we killed them ourselves them on Thursday I felt nothing but confidence in the fact that we were doing the right thing. Yes, it's hard to slit a chickens throat, and yes, it can be kind of disgusting to gut it, but we had raised these chickens as humanely as possible, and we killed them as humanely as well, and if I'm going to be eating meat I feel as if this is something that I should know about and experience.

With that in mind:

CAUTION: some of these pictures are violent and there is also some blood.

VIEWER DISCRETION ADVISED.

|

| Checking the temperature on the scalding box. We borrowed the box and the plucker from a farmer couple we know in town. Thank god, it would have been a pretty impossible task without them. |

|

| The chickens we hung upside in the cones and Dave slit their throats and then let them bleed out into the buckets. |

|

| Then we scalded them for about a minute. |

|

| Then they went into the picker, which spins the chicken around while pulling off its feathers with its black rubber fingers |

|

| Next, we cut off their feet and heads and eviscerated the birds. This is done by cutting a hole around the chicken's vent and extracting their digestive system, heart, liver and lungs. |

|

| Intestines |

|

| Heads and guts |

After we were finished we immediately put the chickens into an ice bath to cool them down. Then, we went back over them with pliers and a hose to pluck out any stubborn feathers and do quality control (double check to make sure all the birds were properly gutted) before drying them off and bagging them up to go into either the refrigerator or the freezer.

We've grilled three chickens to date and they have all been delicious.